Are we just letting this happen again?

Fascism's point of no return

How do ordinary people rationalize the unthinkable? As authoritarianism knocks on the door of American democracy, the history of the Third Reich offers a haunting reflection not of monsters, but of ourselves.

It begins with a feeling of unease. A scroll through a newsfeed, a clip of a rally where the rhetoric feels sharper, the threats more explicit. Until the spear of fascism is pointed at your neck.

We aren't letting this happen again, are we?

For many Americans, the escalating political volatility of the last few years has moved the history of the 1930s from the dusty shelves of academic abstraction into the urgent territory of a survival guide. We watch the polarization, the scapegoating of minorities, and the testing of institutional guardrails, and we ask the inevitable question: Is this how it happens?

But the more haunting question is about those going along, and the millions staying quiet at home.

For decades we've comforted ourselves with the idea that the German people of 1933 were uniquely susceptible to hateful fascism. Brainwashed. Uninformed. Evil. We imagine that we would be different...that we would speak up, that we would resist.

Yet, Third Reich shows that the rise of fascism relies less on a nation of monsters and more on a nation of neighbors. It was built on the banal, terrifying architecture of social conformity, professional ambition, and the human need to belong. To understand how a modern democracy collapses, we must look away from Hitler and toward the ordinary citizen navigating the gray zone between complicity and survival.

The Seduction of the In-Group

If you were a "pure" German in 1933, the onset of the dictatorship might have felt like the lights coming back on. After the humiliation of World War I and the crushing poverty of the Great Depression, the Nazis promised a return to order and the Volksgemeinschaft ("People’s Community").

This was the regime’s most potent psychological weapon. It offered a seductive bargain: equality, status, and belonging for the "in-group," purchased at the price of the "out-group’s" exclusion. Participation was made to feel like a festival. The Winter Relief drives and the Strength Through Joy vacations were communal. They made the average citizen feel seen and valued.

But this belonging was brittle. It required constant maintenance through what sociologists call "ritualistic conformity." The "Heil Hitler" greeting was a social signal. To refuse it was to mark oneself as difficult, a grumbler, an outsider. Most people performed the salute because it was awkward not to. They did it to avoid the friction of social deviance. Over time, however, a psychological mechanism known as cognitive dissonance took hold. It is exhausting to act one way and believe another. Eventually, many aligned their internal beliefs with their external actions. They became what they pretended to be.

The Ordinary Men in the Woods

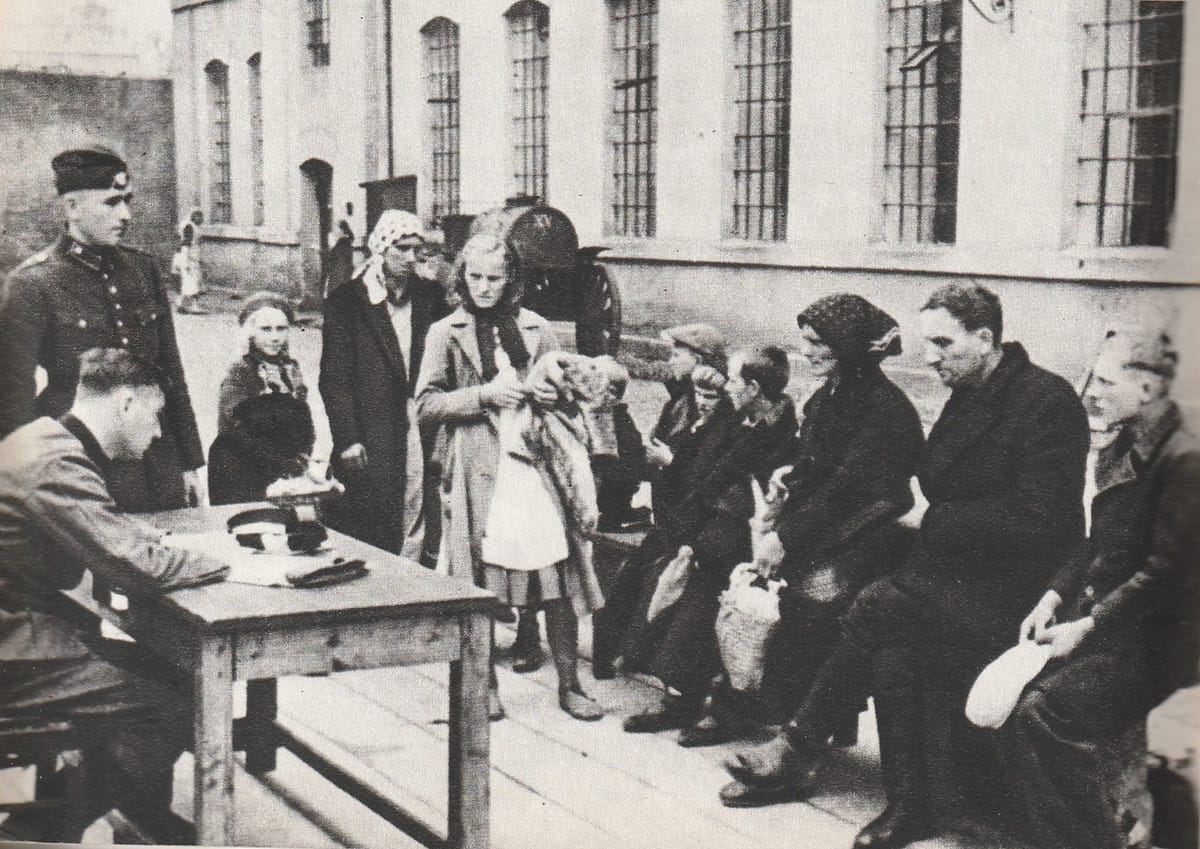

The most chilling dismantling of the "monster" myth comes from a study of Reserve Police Battalion 101. This group was made up of middle-aged, working-class family men from Hamburg, too old for the front lines. In 1942, they were ordered to round up and execute the Jewish inhabitants of the Polish village of Józefów.

Their commander, Major Trapp, weeping and visibly shaken, made an extraordinary offer: any man who did not feel up to the task could step out of line and be assigned other duties. There would be no punishment.

Out of 500 men, only about a dozen stepped forward.

Why? They weren’t all driven by a bloodthirsty antisemitism, though that was part of the cultural air they breathed. They were driven by the fear of looking weak in front of their friends. They didn’t want to leave the "dirty work" to their comrades. They killed out of social deference and peer pressure. The same mundane social glues that keep a high school clique together.

This dynamic appeared even in the highest echelons of society. German doctors performed a psychological process called "doubling." An Auschwitz doctor could supervise the gas chambers by day, selecting thousands for death, and then return home to be a loving father and husband by night. He partitioned his soul, creating an "Auschwitz Self" to handle the horror, keeping his "Prior Self" unpolluted. It was a functional adaptation to evil.

For the millions who were neither killers nor true believers, the primary coping mechanism was Inner Emigration. This was the retreat into the private sphere. You stopped reading the papers. You focused on your garden, your music, your children. You told yourself that by not participating in the worst excesses, you were remaining decent.

The diaries of Victor Klemperer, a Jewish professor in Dresden, document how this silence felt from the other side. He recorded the "mosquito bites" of tyranny and the slow accumulation of indignities. A colleague crossing the street to avoid saying hello. The grocer who apologetically refused to sell him an apple. Fascism didn't require fanatics. Rather, it just needed the population to keep quiet, either through fear or complacency.

For those afraid the terror was real, but it was often self-inflicted. We often imagine the Gestapo as an omniscient surveillance state, but it was surprisingly understaffed and overworked. It relied almost entirely on rats. A neighbor settling a grudge over a shared laundry room, or a colleague eyeing a promotion. The regime weaponized petty envy. It turned the "community" into a panopticon where no one could trust anyone, enforcing a "spiral of silence" where dissent felt dangerous and singular, as if you were the only one who felt that way.

Perhaps the most insidious victory of the regime was its invasion of the family. Through the Hitler Youth, the state offered children power, a rare commodity for the young. It gave them uniforms, purpose, and authority over their parents.

The presence of indoctrinated children blocked the free-flow of communication even within the family home. Parents fell silent at the dinner table, afraid that a grumble about food rationing would be repeated by their son at a Hitler Youth meeting, leading to a knock on the door. Worse, some feared their children would purposefully sell them out. The family was no longer a fortress of truth against the state. Without that, bemoaning of circumstances gradually extinguished.

Was this descent inevitable?

Looking back from the ruins of 1945, it seems so. But history is a series of choices, and there was a moment when the machine could have been stopped.

Consider the Kapp Putsch of 1920. When a right-wing faction tried to overthrow the Weimar government, the response was swift and unified. The trade unions called a general strike. Berlin stopped. Trains didn’t run, water stopped flowing, bureaucrats refused to sign papers. The coup collapsed in days because the ordinary machinery of society refused to cooperate.

In January 1933, Hitler is appointed Chancellor. What if the unions had called a general strike then? By then, however, the voice of the opposition was fatally fractured. The Communists and Social Democrats hated each other more than they feared Hitler. With mass unemployment, workers were terrified of losing their jobs. The psychological moment for collective action had passed.

Also consider the Rosenstrasse Protest of 1943. In the depths of the war, the Gestapo rounded up nearly 2,000 Jewish men who were married to non-Jewish German women. These women marched to the detention center on Rosenstrasse and screamed for their husbands. They refused to leave, even when threatened with machine guns.

And they won. Goebbels, fearing public unrest in the capital, ordered the men released.

Leopold Gutterer, who was Goebbels's deputy at the Propaganda Ministry, later stated in an interview:

"Goebbels released the Jews in order to eliminate that protest from the world. That was the simplest solution: to eradicate completely the reason for the protest. Then it wouldn't make any sense to protest anymore. So that others didn't take a lesson [from the protest], so others didn't begin to do the same, the reason [for the protest] had to be eliminated. There was unrest, and it could have spread from neighborhood to neighborhood ... Why should Goebbels have had them [the protestors] all arrested? Then he would have only had even more unrest, from the relatives of these newly arrested persons." Gutterer also stated: "That [protest] was only possible in a large city, where people lived together, whether Jewish or not. In Berlin were also representatives of the international press, who immediately grabbed hold of something like this, to loudly proclaim it. Thus news of the protest would travel from one person to the next."

It was a demonstration that the regime was not impervious to public pressure, especially from "Aryans." It suggests that the point of no return was further away than we think. Perhaps peaceful, coordinated resistance could have jammed the gears of the Holocaust, had it happened earlier, and on a larger scale.

The tragedy of the Third Reich is that it could have been prevented if it was resisted early enough. Instead, ordinary people did nothing, or did just enough to get by, until the cost of resistance became fatal and complicity was the safest option.

The point of no return was the moment when the fear of social isolation outweighed the moral imperative to speak. It was the moment when the professional civil service decided that swearing an oath to Hitler was preferable to losing a pension. It was the moment when neighbors decided that the apartment of the deported Jewish family was an opportunity to steal their goods, space, job.

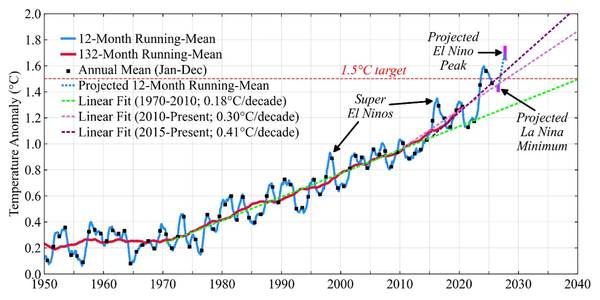

As we wonder why fascism is rising once again, the lesson from Germany is that we should look at the mirror. Authoritarian tendencies exist in any society that values order over justice, and comfort over courage. Occasionally socioeconomic circumstances deteriorate to a point at which these tendencies explode. We are not there yet, as we can see from the massive protests in Minneapolis. Resistance is still an option. A must. But it has a shelf life. It works when the press is still free, when the courts are still independent, and when the unions can still stop the trains.

Once those firewalls burn down, the cost of saying "no" rises from social awkwardness to physical destruction. That day is may come soon, unless we persist.

We'll know all is lost when people stop talking.