New research: 3 degrees by 2050

What It Means for Us

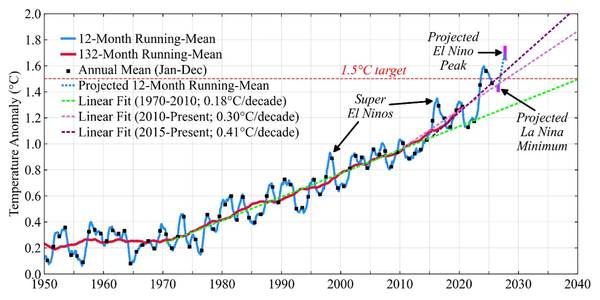

A new study warns that the planet is on track to warm more than three degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2050. This forecast is grounded in a long view of how greenhouse gas emissions have evolved since 1820, compared with our record in improving energy efficiency.

Researchers looked at every major greenhouse gas (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases) as well as emissions from deforestation, farming, and other land-use changes. They found that until well into the 20th century, land-based sources such as forest clearance and agricultural expansion contributed more to global emissions than industry.

They also estimate that technological progress and cleaner energy have cut emissions by around 31 billion tonnes over two centuries, thanks to efficiency gains, shifting away from coal, and the gradual uptake of renewables. Yet these savings were overshadowed by economic growth, which added roughly 81 billion tonnes. Rising affluence has been the dominant driver of emissions increases, outpacing population growth and negating efficiency gains.

Today, producing a dollar of global GDP generates only a sixth of the carbon it did in 1820. But the pace of improvement in reducing the carbon intensity of economic activity (the amount of greenhouse gases emitted per unit of GDP) has slowed since the 1990s.

Meeting climate targets now requires the carbon intensity of GDP to decline 3 times faster than the global best 30-year historical rate (–2.25 % per year), which has not improved over the past five decades. Failing such an unprecedented technological change or a substantial contraction of the global economy, by 2050 global mean surface temperatures will rise more than 3 ◦C above pre-industrial levels.

At current rates of decline in carbon intensity, emissions in 2050 will be high enough to push warming beyond 3 °C. According to the IPCC and other research, this level of warming would cause near-total loss of coral reefs, more than half a metre of sea level rise before 2100, and annual extreme heatwaves across much of the globe.

Severe drops in agricultural yields ( sustained reductions in staple crop production such as wheat, maize, rice, and soy of 10 to 25 percent or more in many regions) are expected in both tropical and temperate zones. Such declines would raise food prices, increase famine, and heighten malnutrition globally. Mortality estimates for a 3 °C world vary, but climate‑related hunger, heat stress, disease, and conflict could kill billions. These impacts are projected to intensify from the 2030s onward, with the most disruptive consequences for human health, livelihoods, and stability appearing by mid‑century, give or take a decade.

The authors avoid prescribing specific hopium-fueled policies but stress that the required changes are without precedent. If global GDP continues to grow at projected rates, achieving climate goals would require an almost six percent annual drop in carbon intensity (a rate no nation has sustained) which they consider highly unlikely. The other alternative: persistent economic contraction over decades, on the order of roughly 1.4 percent decline in global GDP each year, something modern history has never experienced. (Recall the 2008 global GDP contraction was about 2%. Therefore, the required decline would be equivalent to the Great Recession every year. For decades and worsening with time.)

Humanity won't voluntarily do either. Instead, we'll grow until collapse forces the math to work.

Full report: