The Industrial Revolution's warning about AI

What techno-optimists don't want you to know

The cheerleaders of technology insist: Artificial Intelligence will create more jobs than it destroys. They point to the Industrial Revolution as their favorite myth. The tale in which machines lifted humanity into prosperity.

Industrialization, in truth, did not usher in a golden age for most people. It brought disruption, pain, and a redistribution of power so skewed it took generations to correct.

While productivity soared, ordinary workers stagnated in poverty, their labor devalued by the very machines that promised a better world.

Those in power control the means of production and will do anything to control the cost of labor. Any labor-saving technology - machines or AI - will displace labor, even if over the long run associated productivity gains help lift society. The problem is the "long run" can be generations.

Namely, mechanization in the 18th and 19th centuries didn’t instantly enrich the masses. Instead, it destroyed livelihoods.

Skilled artisans were replaced by untrained machine operators, paid a pittance to push levers. The result was not just economic dislocation, but the slow erosion of dignity.

Today, the term "luddite" is used pejoritavely to describe someone who is slow to embrace new technologies. In reality, the Luddites weren’t backward-looking saboteurs; they were skilled professionals driven to desperation. They watched their skills rendered obsolete. All while factory owners raked in the profits. And so, with no union rights, no political recourse, they smashed the machines. Not out of ignorance, but protest. Eric Hobsbawm called it “collective bargaining by riot.”

With less need for skilled labor, factories sought cheap labor to manage the machines. They preferred children and women. Children with nimble fingers. Women who would accept lower pay. By the 1830s, kids made up nearly a third of the factory workforce. They endured long shifts, hazardous conditions, and wages a fraction of what a man once earned. Fathers, once the family’s breadwinner, now watched from the sidelines.

The social structure reoriented. These displaced men didn’t retrain. They didn’t “reskill.” They were casualties of a transformation that had no room for them.

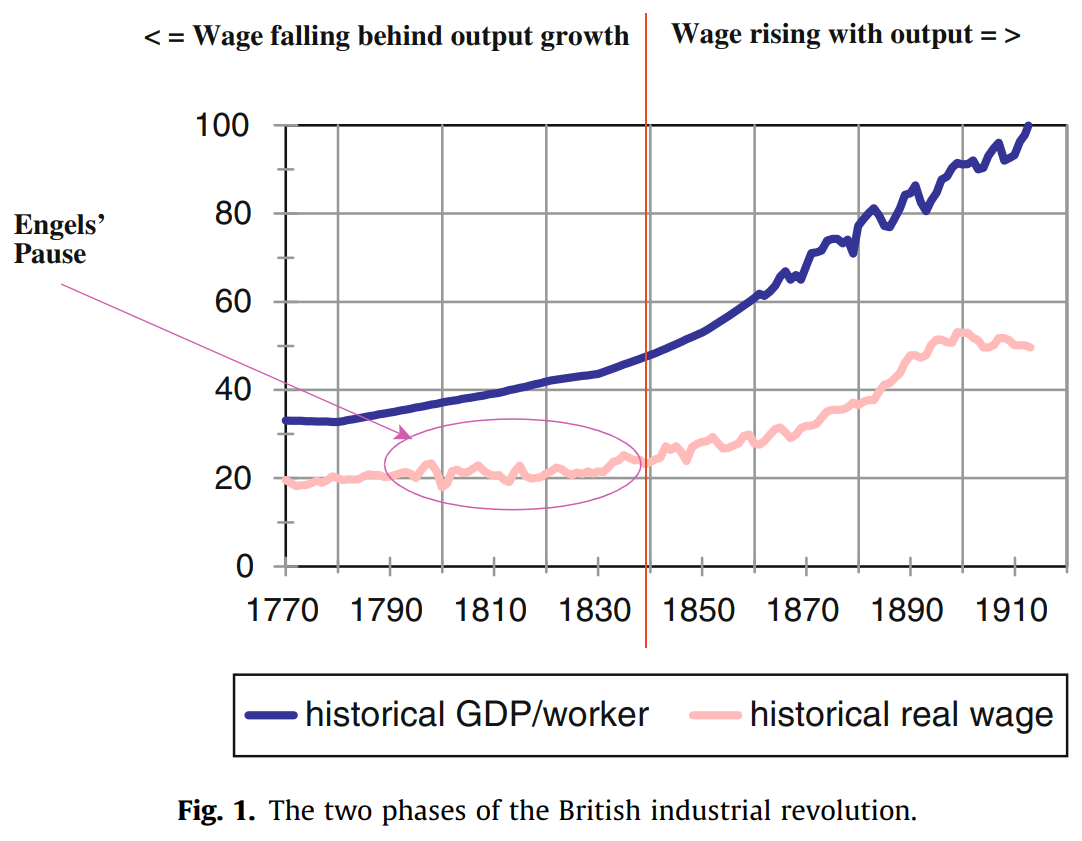

From 1780 to 1840, output per worker (labor productivity) rose nearly 50%. This is because fewer, less expensive women and children could use machines to produce many more widgets.

Meanwhile real wages only rose 12%. All the gains from higher productivity accrued to the owners of capital.

This wasn’t a tide lifting all boats. Economists now call it “Engels’ Pause,” but "pause" downplays the effects. For about half a century, labor’s share of wealth shrank. Capital devoured the spoils.

By 1850, sixty years into the machine age, the average worker was only marginally better off than his grandfather. The real beneficiaries were a narrow elite of factory owners, investors, and landlords.

Eventually, the benefits of industrial mechanization were reaped by broader society. But not first without a long period of pain, poverty, and struggle for most.

In the late 19th century, labor began to improve its standing. After unions, after strikes, after the expansion of suffrage. After workers fought tooth and nail for the right to be seen. After the state, frightened by the specter of revolution, offered scraps of reform to prevent the system from collapsing.

These weren’t gifts. They were concessions.

The vote, labor protections, pensions were not enacted by the invisible hand of capitalism. They were torn from the hands of reluctant elites through the threat of unrest. Social progress was not the outcome of technological progress, although the gains from industrialization provided the means to do so. Rather, social progress was the price of avoiding revolt.

This is the part the techno-optimists never mention.

Across Europe, the story repeated. France, Germany, Russia all saw upheaval driven by the same basic injustice: that industrial growth enriched the few and dispossessed the many. Where reform failed, revolution followed.

The lesson?

Technology does not distribute its gains. Power does.

Left to its own devices, the Industrial Revolution created extreme inequality and intergenerational suffering. What corrected that course was not innovation. It was organizing. Politics. Struggle. Human effort, not mechanical ingenuity.

And even then, the delay was immense.

Wages only began to rise meaningfully after 1850. Middle-class comforts did not widely appear until the 20th century, partly attributable to ongoing productivity gains afforded by the use of fossil fuels.

This is the real story of innovation. Without labor power, it devastates before it ever distributes.

Today, we are told that AI will empower us all. That we should not fear, but embrace the future. But those who say this are forgetting, perhaps conveniently, history. Or worse, rewriting it.

Most of us live comfortable lifestyles, but employability is tenuous. Anyone who's gone through seven interviews for a job knows that power doesn't rest with labor. This will worsen as AI becomes a cheap, highly productive substitute.

If we do not learn from Britain’s long, grim march through industrialization, we will repeat its mistakes.

Who am I kidding? We will repeat the mistakes because thats what those in power want. They're salivating at the thought of running their businesses at a fraction of the cost.

We will watch wages fall as output rises, and living standards collapse. Perhaps the greatest lesson from Engels Pause is that owners of capital can still flourish as skilled labor is demolished. "Who will buy all the stuff" didn't seem to matter as labor was wiped out during the 19th century. (A side project I want to explore more.)

The true legacy of the Industrial Revolution is a warning about our future.